Research Projects

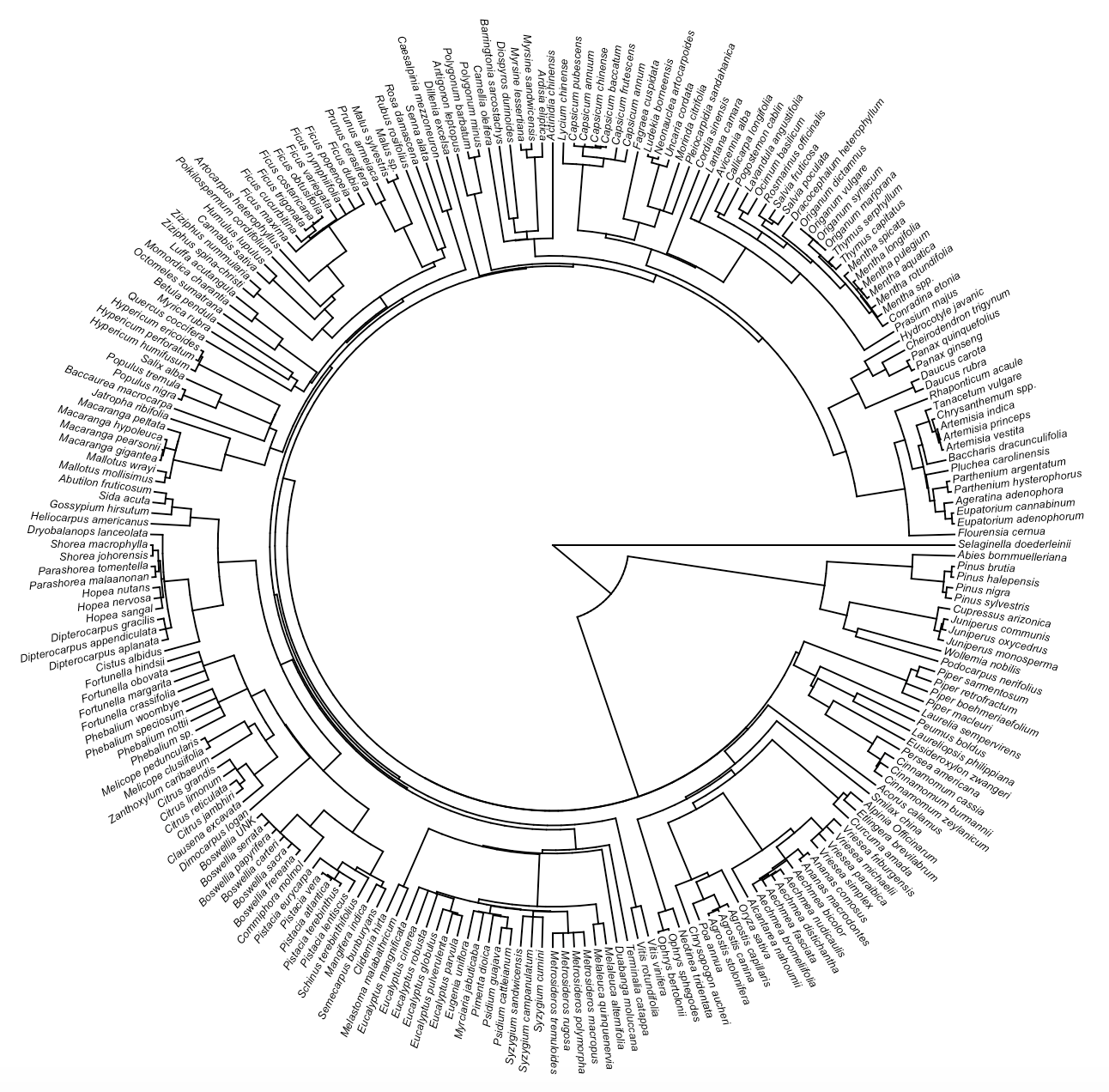

The global distribution of plant terpenes and terpenoids

Ubiquitous and the most diverse set of chemical compounds in plants, terpenes and terpenoids, were considered metabolic ‘waste,’ byproducts from the primary processes plants evolved to grow and reproduce. After decades of inscrutability, the proliferation of molecular techniques, like gas chromatograph-mass spectrometry, unveiled a seemingly unending assortment of these compounds and helped identify their synthesis, chemical properties, and functions. Today, we now know terpenoids make forests more flammable, alarm plants of stress, and carry medicinal benefits for humans.

Phylogeny of plant species represented in a subset of the database.

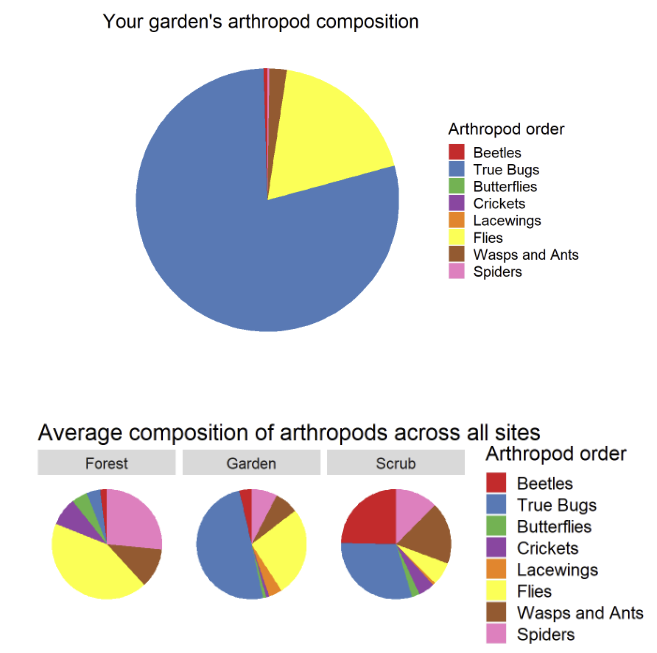

Quantifying the temporal ecology of plant-antagonist interactions

For decades, ecologists in Western science have studied how species and their communities change across time. Time as a unit of measurement and as an axis of understanding the world helps us model species distributions, rates of evolution, phenology and ontogeny, and resource fluctuations. However, we’re still missing examples of modeling impact throughout time that: (a) evaluate impact by modeling shorter time series and (b) manipulate the nature, timing, and frequency of species interactions as priority effects in community ecology. Working with tall goldenrod (Solidago altissima) and its herbivores in common garden and field experiments in southwestern Michigan at Kellogg Biological Station, I ask the following questions:

1. How do single and multiple herbivory events alter host plants and subsequent community ecology?

2. How can we leverage statistical models to evaluate the impact of these interaction events?

How do we leverage field biologists’ quantitative skills for effective public communication?